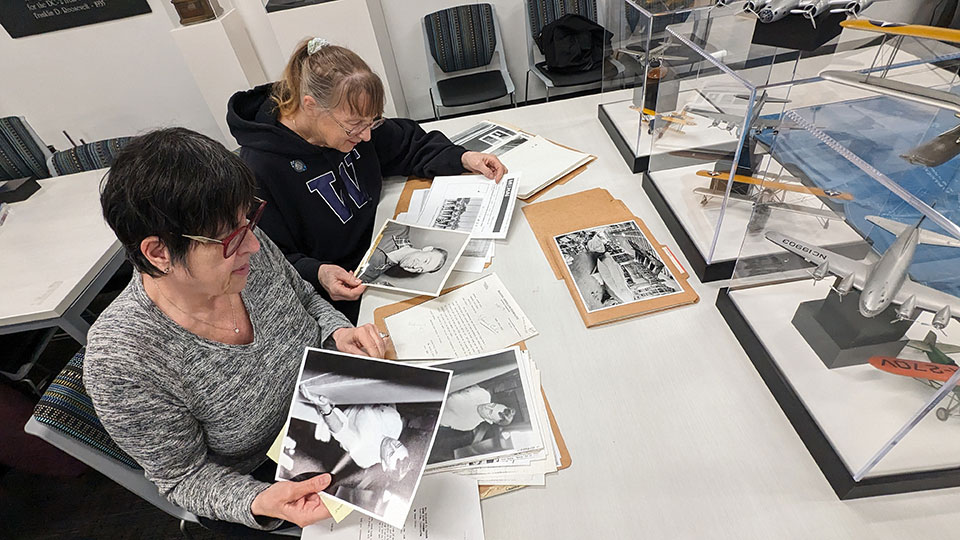

When brothers George and Richard “Dick” Pocock moved to Seattle in 1912 to build racing shells for the University of Washington, they didn’t anticipate where their woodworking skills would take them.

In a copy of his unpublished memoir kept in the Boeing Archives, George describes the unusual circumstances that led the company’s founder, William E. Boeing, to hire the Pococks away from boat building and into aviation history.

It is now early 1916, and one afternoon the president of the university came in the old Tokyo Tearoom shop. He had a gentleman with him.

“These are the boys I was tellin’ you about, Bill,” he said. We had a new finished eight in the shop, which was to go to California. Bill whoever-he-was got under the boat and was on his knees really interested.

“This is the very work I want,” he said to Dr. Henry Suzzallo, the president.

President Suzzallo by now was at the door, tapping the floor with his cane and saying, “Come on, Bill, I must go.”

Bill got up on his feet and started for the door with his hand in his pocket. Taking out his card case, he threw a card on the bench and said, “Come and see me as soon as you can.”

We looked at the card to see who Bill was. The card read W.E. Boeing, Hoge Building, Seattle. We had heard that a man by that name was building a seaplane for his own private use and this undoubtedly was the man.