During his college years, Boeing electrical engineer Patrick Johnson would spend most days on the University of Alabama in Huntsville campus, and most evenings under the hood of one of the many sports cars coming and going from his Decatur, Ala. home’s garage.

By the late 1990s, he had gained a following among local street car enthusiasts who’d seen his custom electronics up close, including controllers paired with nitrous oxide systems for timely jolts of power. For Johnson, who now works in Boeing’s AvionX division, and has spent his entire 20-year career at Boeing, it was the perfect melding of his two passions: fast cars and electronics.

In 2006, while already working full-time at Boeing in Huntsville, an acquaintance approached Johnson about a more complex challenge in the world of motorsports: developing a controller for an electronic fuel injection system used with 2,000-plus horsepower methanol-powered engines.

Within a few months, Johnson and his business partner installed their new system in a Pro Modified-class drag race car. It won its first race at a track in Montgomery, Alabama. At this event, Johnson met an accomplished drag racer and builder in his own right, Dan Parker.

After their win and introduction, Johnson and Parker stayed in touch, occasionally speaking by phone if Parker happened to be working on a car with one of Johnson’s systems.

Eventually, Johnson and his business partner took a step back from their project, which they had grown in their spare time. But it was on the evening of March 31, 2012, on his way home from supporting a customer at a race in Maryland, that Johnson heard the terrible news about his friend. Parker had been in a serious accident.

A 2 a.m. dream

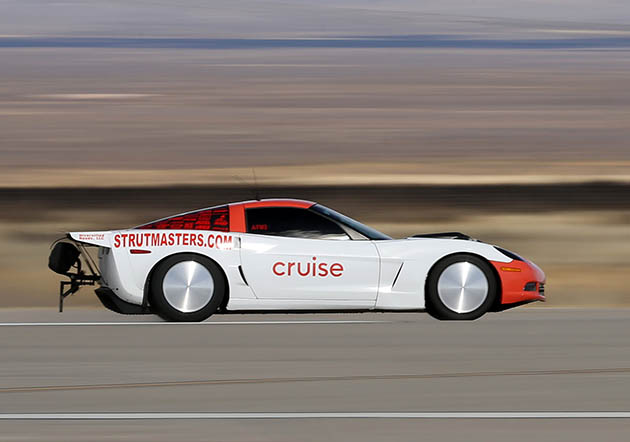

On March 31, 2012, during a race at Alabama Dragway in the town of Steele, Parker was nearing the end of the one-eighth-mile (201-meter) track when his modified 1963 Chevrolet Corvette veered into a concrete retaining wall at about 180 mph (289 kmh). The car burst into flames. Parker narrowly survived the wreck. Two weeks later, he awoke from a medically induced coma with no memory of the accident and having lost his vision. He was told that swelling in his brain had damaged his optic nerve.

For Parker, now 51 and a resident of Columbus, Georgia, racing hadn’t just been a hobby or a vocation before his accident, but a way of life for his family. His father began racing cars at 16. His mother raced at the local dragstrip — even when she was eight months pregnant with Parker. When Parker was eight years old, his dad entered him in his first motorcycle race, and Parker did not disappoint: he finished second in the mini-bike class. At 16, he started racing cars and also building them. As a driver, he would eventually win a Dixie Pro Stock championship and the 2005 ADRL Pro Nitrous world championship title.

In the days, weeks, and months after his spring 2012 accident, Parker struggled to recover from his injuries and come to terms with his new life. As he tells it, he fell into a deep depression.

Late one night in October 2012, Parker laid in bed thinking about his late brother, Chris, who had died tragically of alcoholism three years earlier. When Parker fell asleep at around 2 in the morning, he saw himself racing on the legendary Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah. He was driving a motorcycle. He woke up the next morning and told his fiancée Jennifer about the dream — and that he wanted to become the first blind driver to compete in the time trials on the salt flats. While Jennifer was supportive, not everyone in his immediate orbit bought into the plan. He did his best to tune them out.

“It saved my life,” Parker said during a recent interview about his new goal. “It gave me a purpose.”

The first challenge was to design an audio guidance system that would help Parker steer. In the past, other blind land-speed racers had relied on steering instructions conveyed via two-way radios from team members trailing them in a chase car or helicopter. Parker wanted to drive without the help of a sighted person.

“I thought, ‘Well, who’s the smartest person I know?’” Parker said. “It was Patrick Johnson. I called him and he said ‘That’s easy. I can do it. Start building your motorcycle.’”

With Johnson’s assurances, Parker got to work designing a 70cc, three-wheeled motorcycle. He built most of it in his backyard shop with a mix of parts he purchased himself and those donated to the project. Others volunteered their labor to help, and sponsors also supported the project.

By June 2013, the motorcycle was ready. Parker named it the Christopher Scott Special after his late brother Chris.